Did you know that before I started KunsHuis, I worked at Ogilvy Namibia for five years—years that shaped how I see branding, strategy, and the magic that happens when creativity meets clarity. During my time there I realised just how powerful a creative brief and the briefing session can be. In fact, knowing how to write a creative brief that gets you better designs can be the difference between a project that flows effortlessly and one that feels like an uphill battle.

Recently, I stumbled upon an article in my backups—an absolute gem by Jeremy Diamond (Ogilvy & Mather, New York)—that still holds so much truth today. It gives clear direction on How to Write a Creative Brief That Gets You Better Designs—not the boring, checkbox-style briefs, but the kind that ignite ideas and turn creative teams into powerhouses of innovation.

And I just had to share it.

So, let’s dive into Jeremy’s brilliant insights (with my own thoughts sprinkled in, of course). If you’ve ever struggled with getting a designer to “just get it” or felt like a project was lost in translation, this one’s for you.

Why a Strong Creative Brief Matters

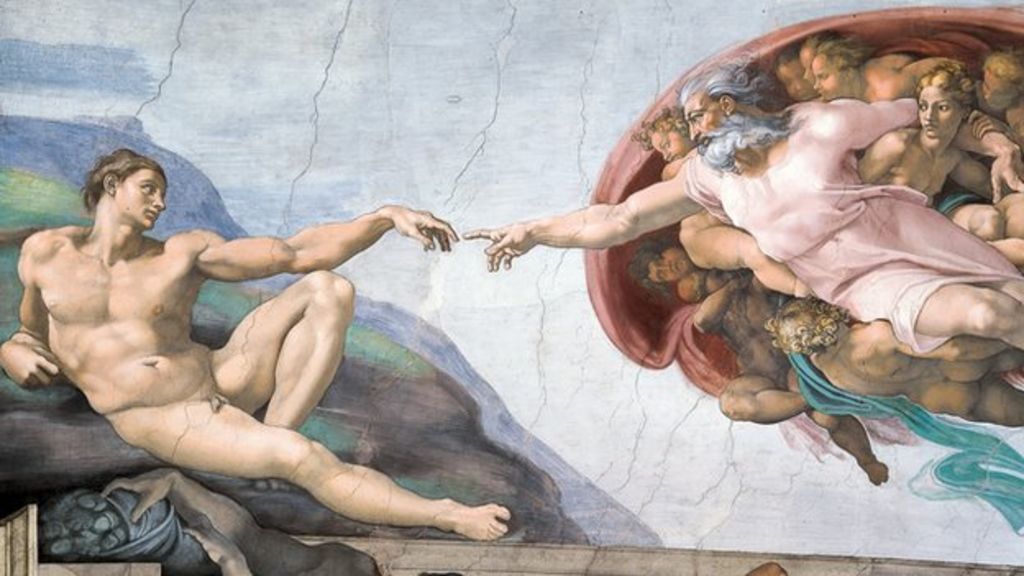

The article from Jeremy described that if the Pope had simply asked Michelangelo to “paint the ceiling,” would we have the Sistine Chapel as we know it?

Probably not.

Pope Julius II didn’t just commission a painting—he gave Michelangelo a vision. He wanted something that would sanctify and celebrate the glory of God.

And that is exactly what a great creative brief does.

It doesn’t just say, “Make it look nice.”

It guides.

It inspires.

It gives the creative mind something to build upon.

That said the Three Things to remember before you Write a Creative Brief That Gets You Better Designs is:

✔️ It states a clear objective.

✔️ It defines the audience’s needs not just demographics, but what they actually care about.

✔️ It establishes the brand’s role in solving those needs.

Most importantly when done well, a brief doesn’t just outline a task, it becomes the springboard for creative ideas that can live across multiple touchpoints.

The Agony and the Ecstasy of the Creative Brief

Creative briefs are one of the most debated topics in advertising and design.

💬 Are they necessary?

💬 What should they include?

💬 Who actually reads them?

At the end of the day cutting to the chase: commercial art isn’t self-expression—it’s problem-solving. Creativity in branding and advertising isn’t about making things pretty—it’s about creating impact, emotion, and action.

And without writing a creative brief that gets you better Designs? That process becomes a guessing game.

Why a Brief Can Make or Break a Project

In fact if Michelangelo had been given a vague brief, we might have ended up with a lovely still-life painting or a pastoral landscape. Thus would that have wowed the Roman churchgoer and stood the test of time?

Nope.

A clear, focused brief allows creatives to go beyond the ordinary and think BIG.

And here’s something no one talks about:

• A great brief isn’t remembered.

• A great creative idea is.

Without a doubt while no one will praise the brief itself, if it’s done well, the work will speak for itself.

What Makes a Brilliant Creative Brief?

Simply put while every project is different writing a creative brief that gets you better designs answers these key questions:

1. What’s the Goal?

Not “make it look nice”—but what action do we want to trigger?

Do we want people to feel something? Buy something? Change behaviour?

2. Who Are We Talking To?

Forget basic demographics—think attitudes, emotions, and motivations. What’s the shared need that this brand can solve?

3. What’s the Brand’s Role?

A brief isn’t just about the product—it’s about why it matters. What gap does this brand fill? How does it make life easier, better, more exciting?

4. What’s the Big Idea?

Every campaign, logo, or design piece needs a hook. What’s the one thing this project should communicate?

5. Why Should People Believe This?

Support your message with proof—facts, emotional truths, or past successes that give people permission to trust the brand.

6. What’s the Brand’s Personality?

Undoubtedly people use products, but they connect with brands. To put it another way what’s the tone, energy, and emotion this brand should evoke?

The Secret to a Great Brief? Focus.

Ever tried catching five tennis balls at once? You’ll probably drop them all.

However if someone throws one, you’ll catch it.

• A bad brief tries to say too much.

• A great brief focuses on one powerful message.

David Ogilvy once said:

“Give me the freedom of a tight brief.”

All in all when a brief is too loose, it doesn’t give creatives direction—it leaves them drowning in uncertainty.

How to Make a Brief Come Alive

A creative brief isn’t just a document—it’s a conversation.

The best briefs don’t come from a boring email thread. They happen in real-life interactions:

• Brief a beer campaign in a bar, not a boardroom.

• In addition talk about trainers while walking through a city.

• Launch a swimwear campaign at the beach.

In fact Creatives work best when they can see, feel, and connect with the brand’s world.

At the end of the day remember: a written brief is great, but a briefing session is better.

The Creative Brief as a Springboard, Not a Rulebook

The best creatives don’t work to a brief—they work from it.

A great brief isn’t about limits—it’s about direction. It should be a launchpad, not a box.

Ultimately if you’re working with a designer, strategist, or copywriter, ask yourself:

Are you giving them clarity—or confusion? Are you throwing them one tennis ball—or five?

Indeed when a brief is done right, creativity doesn’t just follow—it flies.

Want to Take Your Briefs to the Next Level?

I’ve made it easier for you!

My Playbook Planner & Desk include excellent brief templates that help structure projects the right way—from brand identity to campaign design. No more guesswork.

As a gift to you, I’ve put together a free download with all the right questions to ask before any creative project starts. It’s available here:

Love Me, Love Me Not: Why Clients Treat Designers Like Assistants (and How to Change That)

Finally good design starts with good communication—and that starts with Writing a Creative Brief That Gets You Better Designs.

What’s the worst (or best) brief you’ve ever received? Let’s talk in the comments!